HPA Axis and Cortisol Dynamics

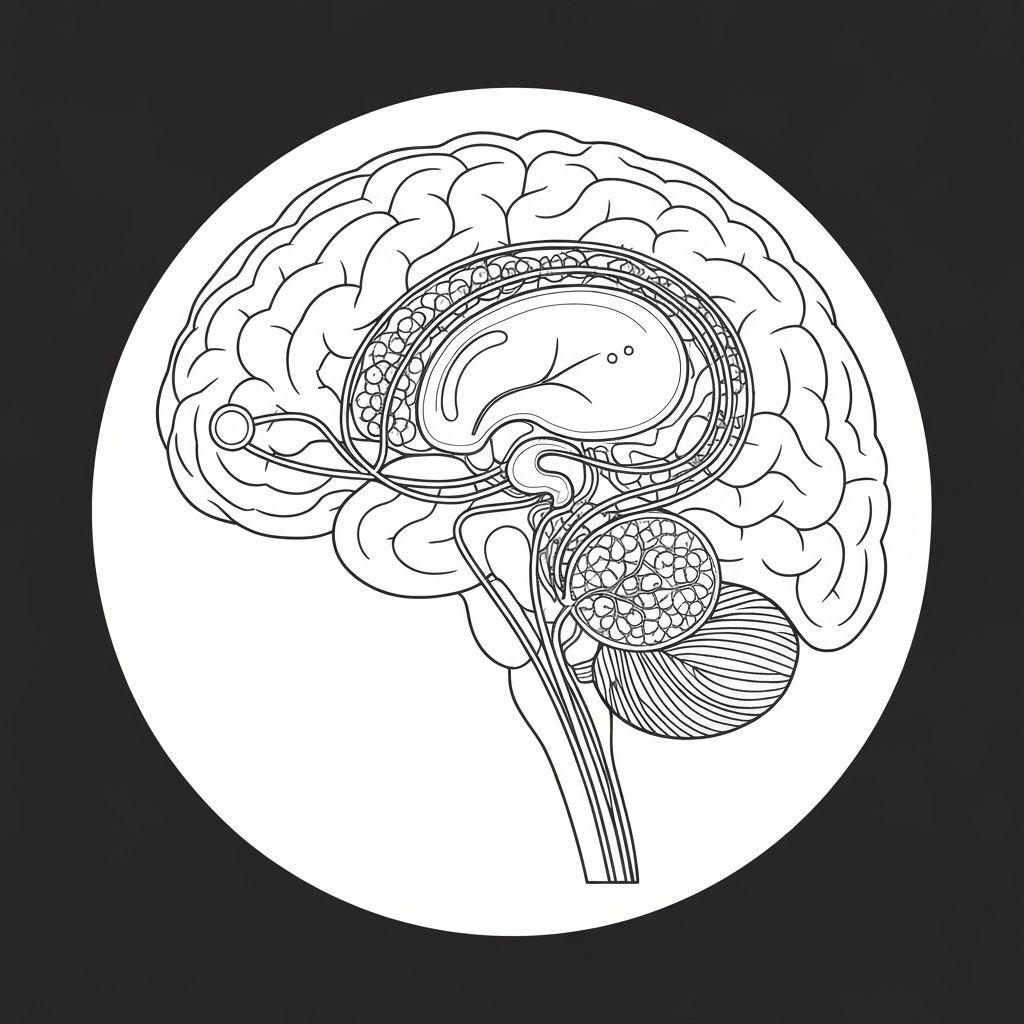

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis represents the central neuroendocrine system governing stress response. When exposed to perceived or actual stressors, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then acts on the adrenal cortex to produce glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol in humans.

This cascade occurs within minutes during acute stress and maintains elevated cortisol patterns during chronic stress exposure.

Glucocorticoid Influence on Appetite Regulation

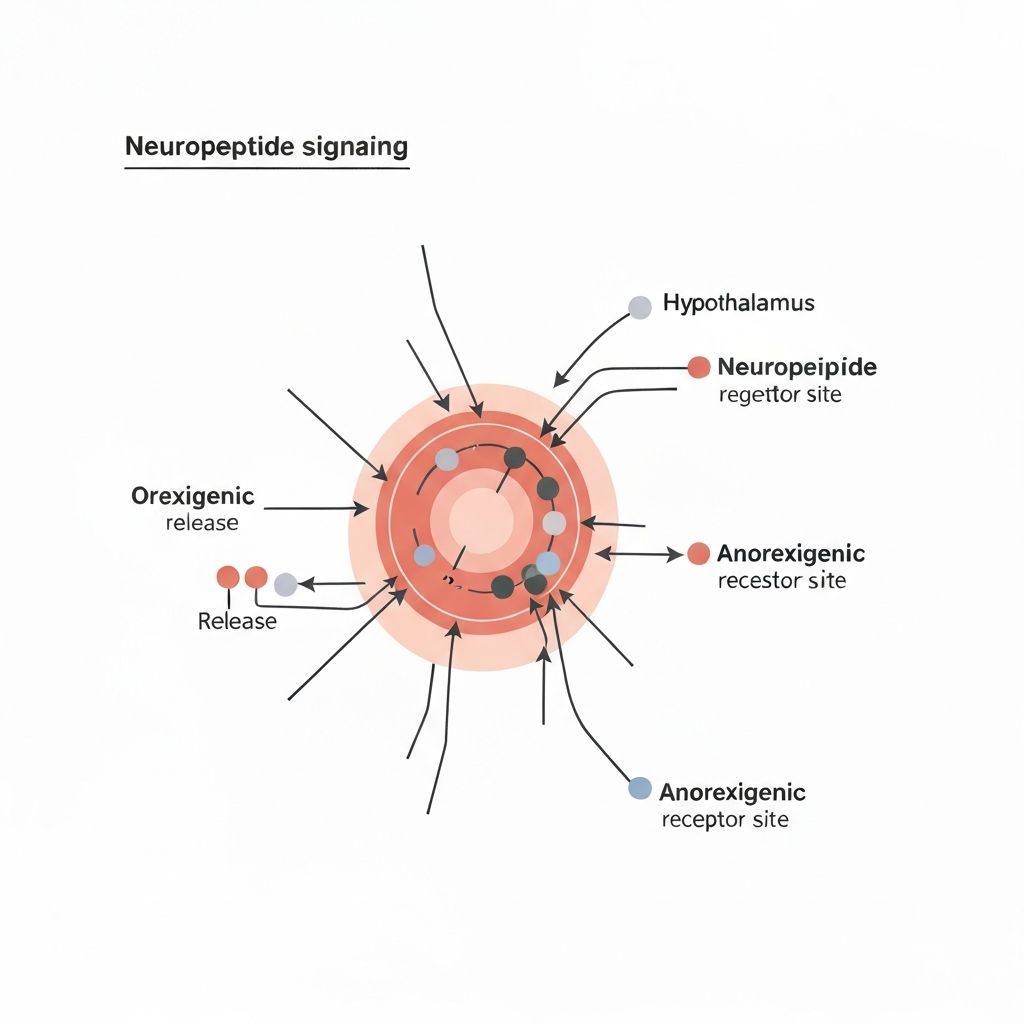

Elevated glucocorticoids, particularly under chronic stress conditions, exert complex influences on appetite-regulating neuropeptides within the hypothalamus. Chronic glucocorticoid exposure increases expression and activity of neuropeptide Y (NPY), a potent orexigenic (appetite-stimulating) peptide, whilst simultaneously reducing pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) activity, which normally suppresses appetite.

This neurochemical shift creates a state favouring increased energy intake signalling.

Visceral Fat Accumulation Patterns

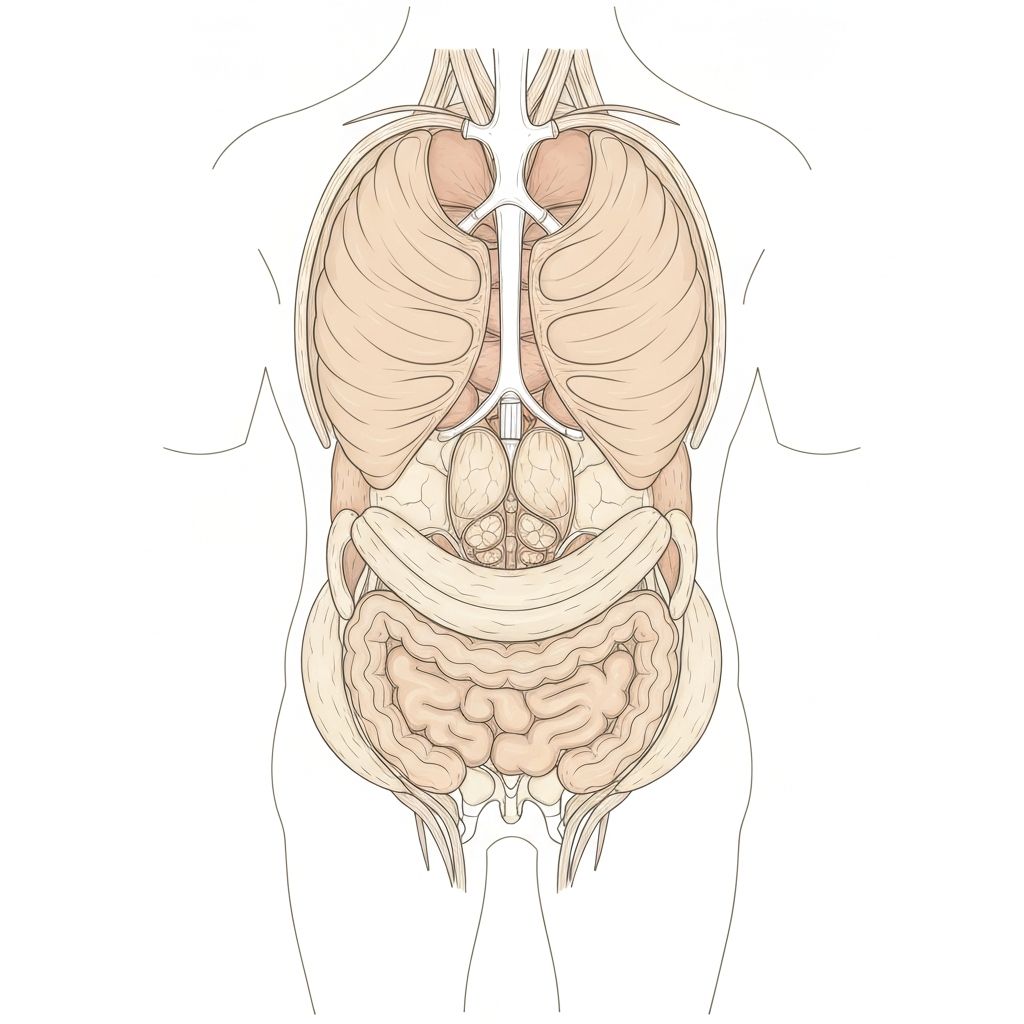

Chronic glucocorticoid exposure preferentially promotes the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue—fat stored around abdominal organs—rather than subcutaneous adipose tissue beneath the skin. This preferential distribution pattern occurs because glucocorticoid receptors are expressed at higher density in visceral adipose tissue and because cortisol's metabolic effects favour visceral deposition over subcutaneous deposition.

Visceral adipose tissue exhibits distinct metabolic and inflammatory characteristics compared to subcutaneous stores.

Food Reward Sensitivity Under Stress

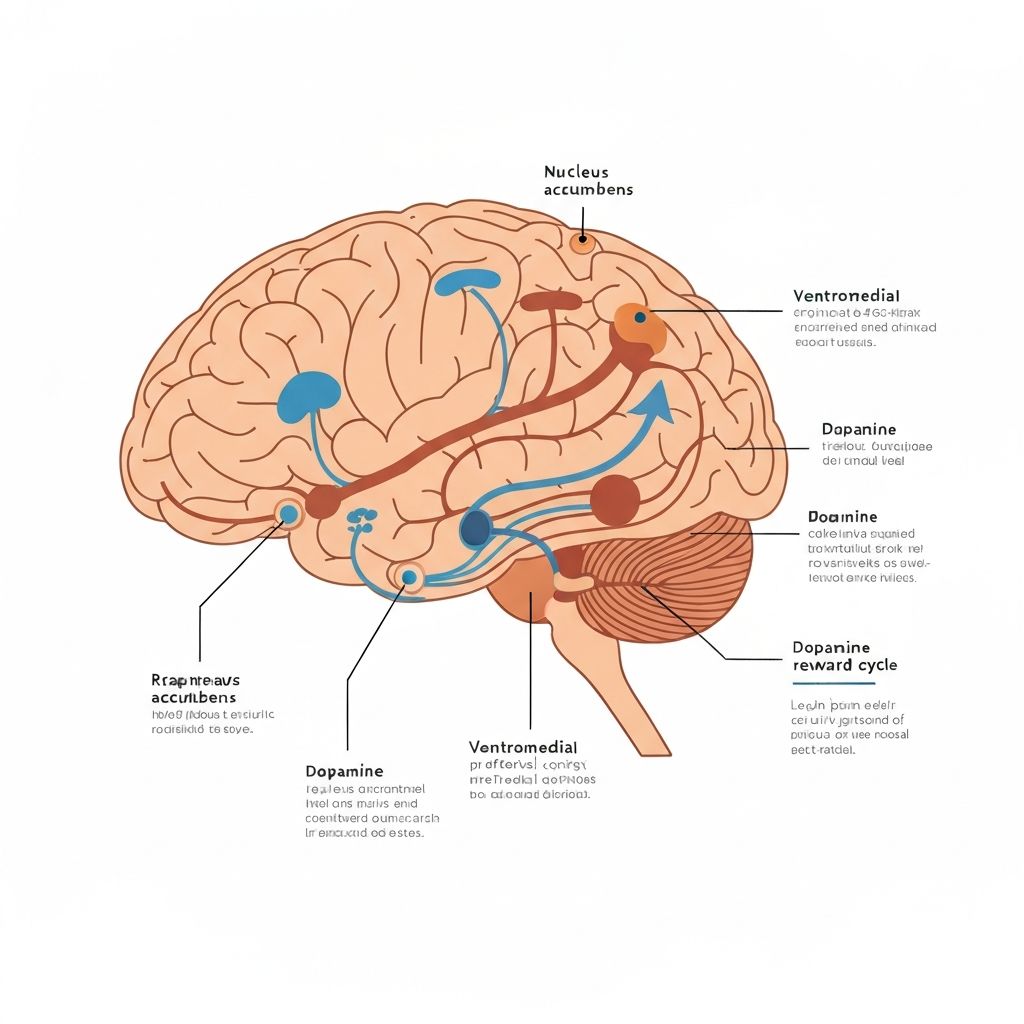

Chronic stress alters the sensitivity of reward-processing neural circuits, particularly within the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and striatum. Stress-induced changes in dopamine and opioid signalling increase the hedonic value—subjective pleasantness—of highly palatable foods rich in fats and simple carbohydrates whilst potentially reducing the reward salience of nutrient-dense options.

This shift in food preference patterns represents a measurable change in how the brain evaluates food choices.

Sleep and Circadian Disruption Effects

Chronic stress frequently disrupts both sleep architecture and circadian rhythm timing. Elevated glucocorticoids suppress melatonin production and destabilise circadian phase, whilst hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system fragments sleep. Sleep loss and circadian misalignment independently impair glucose regulation, increase ghrelin (appetite-stimulating hormone) secretion, suppress leptin (appetite-suppressing hormone), and shift metabolic substrate utilisation toward increased fat storage.

Behavioural Patterns Associated with Chronic Stress

Beyond neuroendocrine mechanisms, chronic stress correlates with altered behavioural patterns including emotional eating (consuming food in response to negative emotional states rather than physiological hunger), reduced physical activity and exercise engagement, impulsivity in dietary choices, and reduced inhibitory control over intake. These behavioural shifts contribute significantly to shifts in overall energy balance and food selection patterns.

Observational Cohort Data

Population-based cohort studies and cross-sectional surveys consistently document associations between perceived stress levels and longitudinal weight trends. Individuals reporting chronic psychological stress show higher mean body weight, greater weight gain over follow-up periods, and higher waist circumference compared to low-stress counterparts. However, these associations remain complex and are mediated by multiple overlapping physiological, behavioural, and environmental factors with substantial individual variability.

Experimental Stress Manipulation Findings

Laboratory studies employing acute and chronic stress manipulations in controlled settings document measurable changes in energy intake, food choice, substrate metabolism, and energy expenditure. Acute stress sometimes reduces immediate intake (through sympathetic activation) but frequently increases subsequent intake, particularly of palatable foods. Chronic stress models consistently show sustained increases in intake, preferential selection of energy-dense foods, and metabolic shifts favouring fat storage—though magnitude varies substantially across individuals.

Individual Differences in Stress Responsivity

Substantial heterogeneity exists in how individuals respond physiologically and behaviourally to stress. Genetic polymorphisms affecting HPA axis sensitivity, glucocorticoid receptor function, and dopamine signalling create biological predispositions toward differential stress reactivity. Environmental and developmental factors, including early-life stress exposure and chronic adversity, shape long-term stress response patterns and allostatic load—the cumulative physiological wear from chronic activation of stress systems. These individual differences contribute importantly to variability in stress-associated weight and metabolic outcomes.

Detailed Stress-Physiology Explorations

HPA Axis Activation and Cortisol Secretion Patterns

Detailed examination of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis structure and function, cortisol circadian patterns, and acute stress-induced activation.

Explore this connection →Glucocorticoids and Appetite Neuropeptide Regulation

In-depth analysis of how glucocorticoids modulate NPY and POMC expression, and the downstream effects on appetite signalling.

Explore this connection →Stress-Induced Visceral Adipose Tissue Accumulation

Comprehensive overview of visceral fat biology, glucocorticoid receptor distribution, and mechanisms favouring visceral adiposity under chronic stress.

Explore this connection →Changes in Food Reward and Palatability Preference

Detailed examination of stress-induced alterations in reward sensitivity, hedonic value assessments, and food choice biases.

Explore this connection →Circadian and Sleep Disruption in Chronic Stress

In-depth analysis of stress effects on sleep architecture, circadian timing, and secondary metabolic consequences.

Explore this connection →Individual Variability in Stress Responsivity and Allostatic Load

Exploration of genetic and environmental factors creating individual differences in stress response and cumulative physiological wear.

Explore this connection →

Frequently Asked Questions

Chronic stress does not universally cause weight gain—individual responses vary substantially. Stress influences multiple physiological, metabolic, and behavioural pathways that collectively shift energy balance patterns for many individuals, but the magnitude and direction of change depends on individual biology, existing metabolic state, behavioural responses, dietary environment, and numerous other factors. Some individuals experience weight gain under chronic stress, whilst others maintain stable weight or experience loss.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is the body's central stress response system. It coordinates the release of cortisol and other glucocorticoids during stress. Understanding the HPA axis is important for comprehending how stress signals translate into physiological changes affecting metabolism, appetite, sleep, and immune function. The HPA axis represents one of the key mechanisms linking psychological stress to physiological changes.

Glucocorticoids like cortisol act on hypothalamic neural circuits to increase activity of appetite-stimulating neuropeptides (particularly neuropeptide Y) whilst decreasing appetite-suppressing peptides (such as POMC-derived peptides). This neurochemical shift creates a net increase in appetite signalling and drive to consume food. The effects are dose and duration dependent, with chronic elevation producing sustained increases in appetite drive.

Visceral adipose tissue expresses glucocorticoid receptors at higher density than subcutaneous tissue, making it more responsive to cortisol's metabolic effects. Additionally, cortisol's biochemical actions—including increased lipoprotein lipase activity and reduced triglyceride clearance—favour fat deposition in visceral depots. This preferential accumulation pattern occurs despite total energy intake, representing a shift in where excess energy is stored.

Stress alters reward-processing circuits in the brain, increasing the hedonic value (pleasantness) of highly palatable, energy-dense foods whilst potentially reducing appeal of nutrient-dense options. This creates a shift toward preference for foods high in fats and simple carbohydrates. The effect appears mediated through changes in dopamine and opioid signalling in reward-sensitive brain regions.

Yes. Chronic stress disrupts both sleep quality and circadian timing. Sleep loss independently increases ghrelin (appetite-stimulating hormone) secretion, decreases leptin (appetite-suppressing hormone), impairs glucose regulation, and shifts metabolic substrate utilisation. These sleep-related changes contribute meaningfully to altered energy balance patterns observed during chronic stress.

Emotional eating—consuming food in response to negative emotional states rather than physiological hunger—frequently accompanies chronic stress. Stress activates brain regions associated with emotion regulation, and food consumption (particularly palatable foods) can temporarily modulate negative emotional states through reward system activation. This behavioural pattern contributes to increased overall energy intake during stressful periods.

Cortisol does not directly convert consumed food into fat cells. Rather, cortisol modulates multiple metabolic pathways including glucose metabolism, substrate utilisation during fasting, and the activity of enzymes involved in fat storage. These effects shift the overall metabolic environment toward net fat accumulation, particularly in visceral depots, especially when combined with increased energy intake and reduced activity.

Stress-induced physiological changes are often reversible when stressors are removed and normal HPA axis function is restored. However, the duration and intensity of prior stress exposure influence the time course of recovery. Some individuals show rapid normalisation of appetite, sleep, and metabolic patterns following stress cessation, whilst others experience more prolonged adaptation periods. Tissue remodelling, such as changes in adipose tissue distribution, may persist longer than neuroendocrine normalisation.

Individual differences in stress responsivity are substantial. Some individuals show blunted HPA axis activation or reduced sensitivity to glucocorticoids, limiting physiological changes in appetite and metabolism. Additionally, behavioural responses to stress vary—some individuals respond with reduced appetite or increased physical activity. Genetic factors, prior stress exposure history, baseline metabolic health, and environmental factors all contribute to creating individuals with vastly different stress-weight associations.

The physiological mechanisms described here represent research-derived understanding of general patterns. However, individual stress responses, metabolic characteristics, and life circumstances vary enormously. This educational content describes general biological principles but does not constitute personal medical, nutritional, or psychological guidance. For personalised recommendations relevant to your specific situation, consult qualified healthcare or mental health professionals.

This site provides educational overviews of stress-metabolism connections. For deeper exploration, see the detailed explorations pages linked under "Detailed Stress-Physiology Explorations" above. Academic resources include peer-reviewed journals in psychoneuroendocrinology, neuroendocrinology, and stress physiology. Textbooks on neuroendocrinology and stress biology provide comprehensive foundations. Consult qualified professionals—endocrinologists, neuroscientists, or psychologists—for research-guided discussion of specific topics.

Continue Your Exploration

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

Discover more detailed information about the physiological mechanisms linking stress and energy homeostasis through our comprehensive explorations.

Explore neuroendocrine regulation topics →