HPA Axis Activation and Cortisol Secretion Patterns

Educational exploration of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis structure, function, and cortisol dynamics.

Overview of the HPA Axis

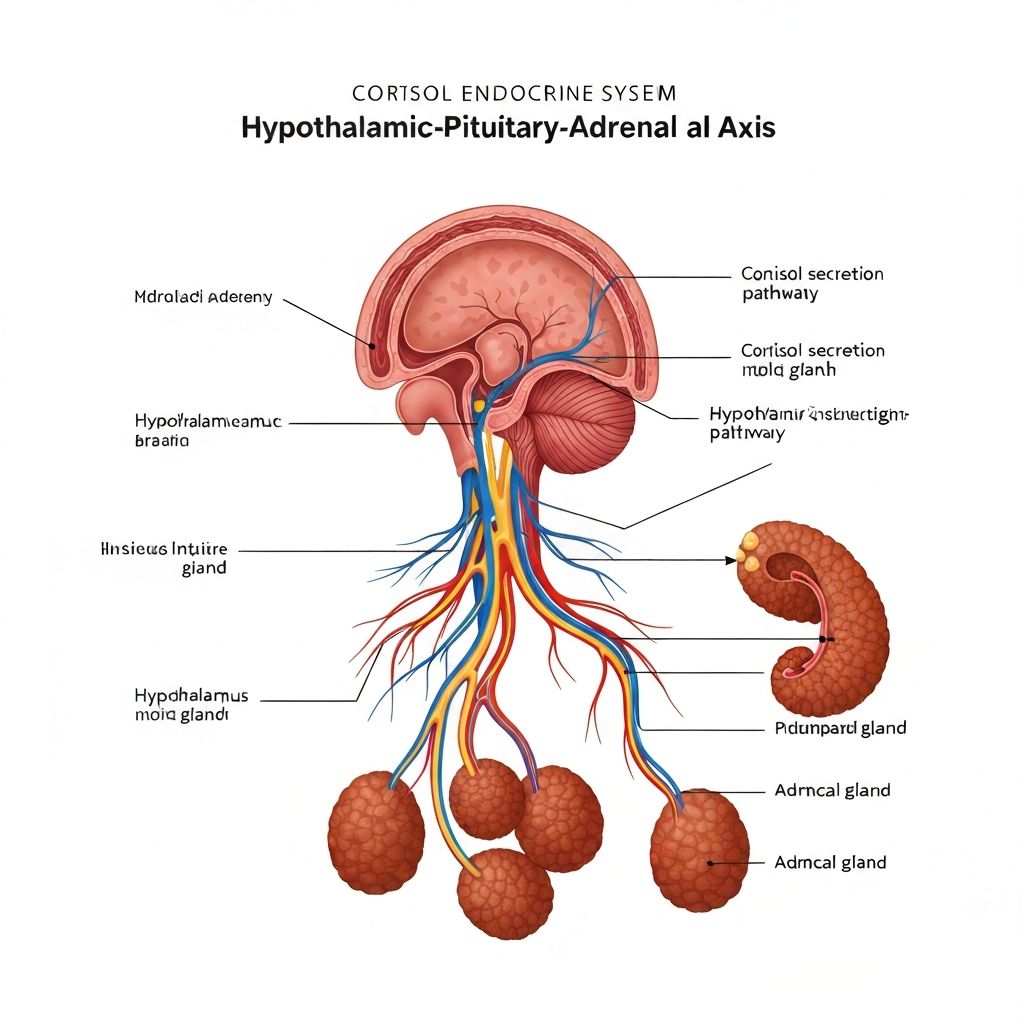

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis represents one of the body's primary stress response systems. It comprises three interconnected endocrine glands: the hypothalamus (a region of the brain), the anterior pituitary gland (attached to the brain's base), and the adrenal cortex (the outer portion of the adrenal glands sitting atop the kidneys). These three structures form an integrated circuit that coordinates the release of stress hormones in response to perceived or actual environmental or psychological threats.

Understanding HPA axis function is essential to comprehending how psychological stress translates into physiological changes affecting metabolism and energy regulation.

The Stress Response Cascade

When the central nervous system detects a stressor, a coordinated sequence of events unfolds. First, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), a neuropeptide that travels through the bloodstream to the anterior pituitary gland. CRH stimulates specialised cells within the pituitary (corticotroph cells) to synthesise and release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then enters the bloodstream and travels to the adrenal glands, where it stimulates the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex to produce and release glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol in humans and other primates.

Cortisol Circadian Rhythm

Under normal, non-stressed conditions, cortisol secretion follows a robust circadian (approximately 24-hour) pattern. Cortisol levels typically peak in the early morning hours (approximately 30–60 minutes before waking), facilitating arousal, alertness, and mobilisation of energy substrates for daytime activity. Cortisol levels gradually decline throughout the day, reaching their nadir (lowest point) in the late evening, approximately 2–3 hours after sleep onset. This circadian pattern is generated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the brain's master clock, and is entrained (synchronised) by light-dark cycles, meal timing, and activity patterns.

Acute Stress Response

During acute stress exposure, the HPA axis is activated, causing a rapid increase in circulating cortisol within minutes. This acute elevation reflects increased synthesis and release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex in response to the elevated ACTH signal. The magnitude of cortisol elevation depends on the intensity and perceived significance of the stressor. In response to acute physical or psychological challenge, cortisol levels can rise two to three-fold or higher within minutes, providing metabolic mobilisation for immediate coping responses.

Chronic Stress and HPA Axis Adaptation

With sustained stress exposure, HPA axis function undergoes adaptational changes. Chronic stress can produce sustained elevations in basal cortisol levels, flattening of the normal circadian rhythm, and alterations in the responsivity of the HPA axis to additional stressors. Some individuals develop a blunted cortisol response to stress (decreased reactivity), whilst others show an exaggerated or prolonged response. These adaptational patterns vary between individuals and depend on factors including the chronicity and nature of stressors, prior stress exposure, genetic factors, and individual differences in stress sensitivity.

Negative Feedback Regulation

The HPA axis employs negative feedback regulation to prevent excessive cortisol elevation. Elevated cortisol levels inhibit further CRH release from the hypothalamus and ACTH release from the pituitary, thereby reducing additional cortisol secretion. This feedback mechanism normally maintains HPA axis stability and prevents unlimited cortisol escalation. However, in chronic stress, this negative feedback regulation can become desensitised or blunted, allowing sustained elevation of cortisol despite the presence of elevated levels—a phenomenon termed "glucocorticoid resistance" in some contexts.

Cortisol's Metabolic Actions

Cortisol acts through glucocorticoid receptors distributed throughout the body to mobilise energy stores and shift metabolism. Cortisol promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis (glucose synthesis from non-carbohydrate substrates like amino acids and glycerol), increases lipolysis (fat breakdown), and generally shifts the metabolic environment toward increased glucose and fatty acid availability in the bloodstream—appropriate for acute physical or psychological demands but potentially metabolically disruptive if sustained chronically.

Research Context

Extensive research using salivary cortisol collection, blood sampling, and urinary cortisol metabolite analysis has documented HPA axis responses to various stressor types, individual differences in responsivity, and long-term consequences of chronic HPA axis activation. Studies indicate that HPA axis function can be reliably measured and that meaningful individual differences exist in both baseline activity and reactive responsivity.

Important Note: This information is educational only. It describes general physiological mechanisms but does not constitute medical advice. Individual stress responses vary substantially. Consult qualified healthcare professionals for concerns about your health or stress.